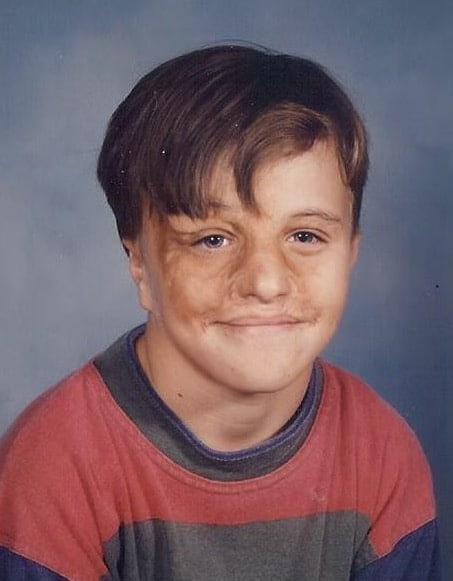

At fourteen months old, a stranger’s rage pressed Keith Edmonds’ face against an electric heater. Third-degree burns devoured half his face. Doctors didn’t expect him to live through the night. He did—then spent years at the Shriners Burn Institute in Cincinnati, enduring surgery after surgery just to approximate “normal.” Childhood offered no soft landing. He went into foster care, waited to be reunified with his mother, and learned his attacker received only ten years in prison. Kids stared. Some were cruel. By thirteen, he was drinking to mute the noise, a habit that followed him into his twenties with depression, addiction, and too many bad nights.

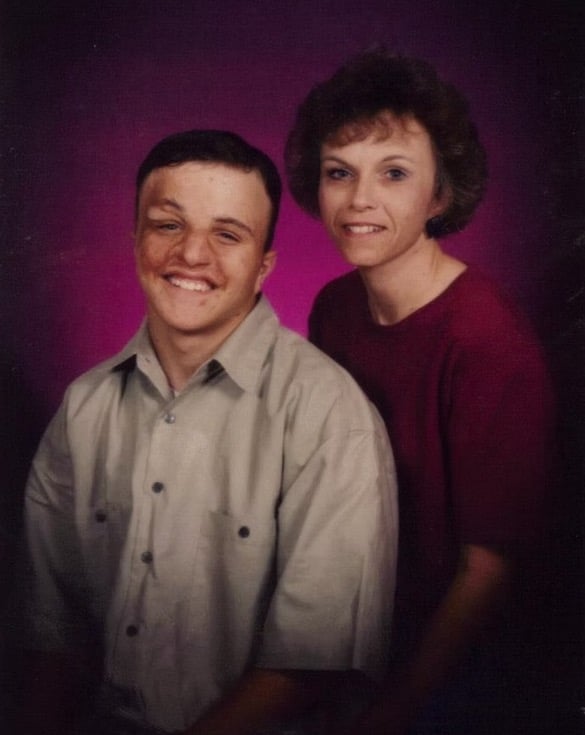

On his 35th birthday—July 9, 2012—something inside him snapped into focus. Mid–drinking binge, he decided he was done. He wanted to become a better person. He got sober and rebuilt from the ground up. Keith found his footing in corporate sales, first at Dell, then at The Coca-Cola Company, where he earned top honors and was trusted with the toughest inner-city Detroit route. People who didn’t trust easily trusted him. The scars on his face told a truth his words didn’t have to: he knew pain, and he wasn’t going to waste it.

In 2016, he turned that truth into action and launched the Keith Edmonds Foundation to empower abused and neglected kids. Backpacks of Love gives foster children essentials for their first days in care. Camp Confidence pairs survivors with mentors, builds skills, and—maybe most important—offers a place to be seen. He refuses to make it a drive-by kindness. “We can’t just come into their lives for the camp and then leave,” he says. “We walk alongside them.” The impact is immediate and personal. A high school principal in Tennessee put it simply: students believe him because he wears his scars every day and never feeds them platitudes. One girl, teetering on the edge, met Keith and his wife, Kelly, and “became like a new kid.” Hope showed up on her face again.

Keith understands why. “Some people wear their scars all on the inside. I wear mine inside and out.” Sobriety, he says, is for every child who’s been hurt by abuse. He knows where his attacker lives now. He hasn’t gone to see him. Forgiveness, he’s learned, doesn’t excuse the harm or erase the memory—it frees the one carrying it.He still talks to his mother. The years weren’t easy, but he chose to let forgiveness have the last word. He even wrote the story down—Scars: Leaving Pain in the Past—because he knows there’s a kid out there who needs proof that the worst day of your life doesn’t get to be the author of the rest.

From a toddler fighting for breath to a man handing it back to others, Keith’s journey isn’t neat, but it’s true. He traded revenge for purpose, addiction for service, surviving for lifting others. And every time a child shoulders a backpack, finds a mentor, or hears, “I’ve been where you are,” his scars do what they were never meant to do: they heal.