On the streets of wartime London, with the threat of bombing and destruction looming over their heads, many Brits and Allied troops did the unexpected – attend a burlesque show. The Windmill Theatre, located in the city’s West End, became a popular place to visit during the war because it simply refused to close.

Setting up the show

The building, initially known as the Palais de Luxe, was purchased by Laura Henderson in 1931 and renamed the Windmill Theatre. Henderson hired Vivian Van Damm to act as the manager and produce new shows.

The theater became famous for creating a burlesque show called Revudeville, which was a form of continual variety show which came to include nude tableau vivants – naked women posing without moving. Performances ran six days a week, upwards of five times a day, with no break in-between shows.

Laura Henderson taking coffee with the girls during a break in rehearsals, August 1943. (Photo Credit: Daily Mirror / Mirrorpix / Getty Images)

The Windmill Theatre’s Revudeville was a unique show, as there were very strict rules for on-stage censorship in Britain. West End theaters were censored by Lord Chamberlain (then Lord Cromer). Van Damm convinced Lord Cromer that the nudity within the Windmill Theatre was no different than that which was present in famous artwork that was not censored.

Lord Cromer ruled that he would allow the theater to include nudity in their shows, so long as it was a tableau vivant – a static scene – where the women couldn’t move. Cromer famously asserted that “if you move, it’s rude.”

Windmill Girls performing Paris by Night… Before 1940 at the Windmill Theatre. (Photo Credit: Tunbridge / Tunbridge-Sedgwick Pictorial Press / Getty Images)

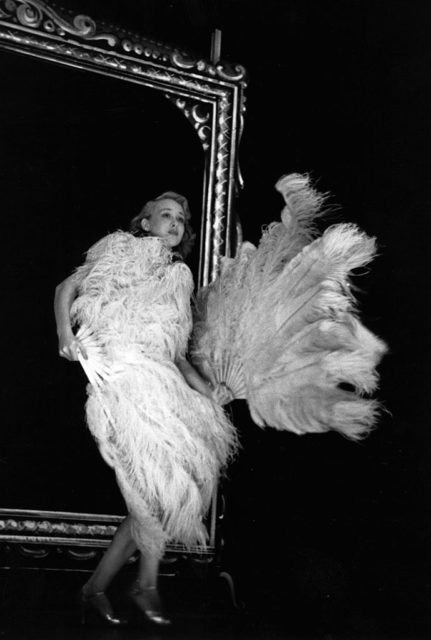

The nude women were incorporated into the show in creative ways, which gave the audience an illusion they were moving, while still complying with Lord Cromer’s rule. In some instances, they stood on a platform, which moved to show different angles. In others, they’d be revealed to the audience by moving feather fans that other performers held to cover different parts of their bodies.

The incorporation of nudity into the show is what pushed these women into the spotlight as the legendary “Windmill Girls.”

The Blitz

The Windmill Theatre became more famous during the Second World War, when Henderson made the decision to keep it open throughout the Blitz, the heavy bombing campaign conducted by Germany against the United Kingdom. The Blitz occurred between September 7, 1940 and May 11, 1941, with the Germans targeting strategic cities throughout Britain.

While they dropped bombs across the country, the air raids were heavily focused in London, as it was Britain’s capital city. In response to the bombings, citizens quickly got used to responding to air raids on a frequent basis.

Windmill Girl dancing with ostrich feather fans. (Photo Credit: Bert Hardy / Getty Images)

Between the Blitz and a series of attacks in 1944, roughly 12,000 metric tons of bombs were dropped on the city, and nearly 30,000 people were killed. Since it stayed open throughout the attacks, the Windmill Theatre earned the popular slogan “we never closed.” Patrons humorously adapted their slogan to “we never clothed.”

The only time the theater closed during the entire war was prior to the Blitz, when London instituted a mandatory 13 day closure of theaters in September 1939.

Performing during the Second World War

Through the worst of the air raids, many of the dancers and theater staff moved into the Windmill Theatre to live full time. They were able to take shelter in the lower floors during bombings in order to stay safe. The women who worked there were well looked after by management during this time.

Windmill Girls living in the theater during the Blitz. (Photo Credit: Hulton-Deutsch Collection / CORBIS / Getty Images)

It was run much like a boarding school, with strict rules on drinking, lights out and separating the female performers from the men. Referring to an interview with surviving Windmill Theatre dancers, Stephen Frears said, “All they ever said was it was like a family—they just had such a wonderful time there. And they used to talk about it as if it was the most wonderful family that they’d fallen into.”

Despite the dangers Londoners faced throughout the raids, the shows continued drawing in large crowds particularly from troops on leave from the war. Since the shows took place back-to-back throughout the day, many eager patrons would stay to watch more than one show.

Those who were seated at the back of the theater for the first show would make a rush to the front for the second once those seats were vacated, becoming known as the “windmill steeplechase.” Once the second show started, these patrons would be in what was called the “full sight seats,” where they were seated so close to the stage that they could almost touch the performers.

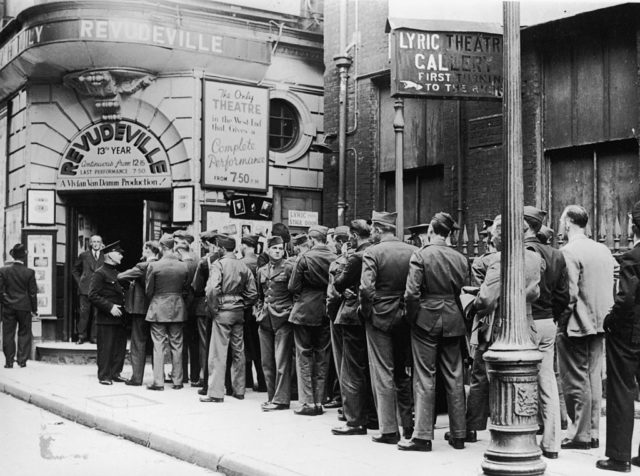

A queue, composed mainly of American servicemen, waiting to enter the Windmill Theatre in London for a performance of the Revudeville, September 1944. (Photo Credit: Keystone / Getty Images)

Not only did the dancers keep up the morale of citizens and troops through their continuous performances, they were also rotated through fire watch on the roof of the theater. If they noticed German bombers overhead while the show was on, performers and patrons were moved down to the safety of the building’s lower levels.

While the women were on watch for air raids, and the theater itself was never hit, that didn’t stop there being several close calls.

Air raid warden Judy McCrea puts on makeup while on duty at Paddington. She was a showgirl at the Windmill Theatre in London. (Photo Credit: William Vanderson / Fox Photos / Getty Images)

These prompted a number of iconic moments for theater-goers and were some of the only times the performers broke the “no movement” rule. In one instance, the detonation of a bomb near the theater caused plaster and debris to rain down, but when the debris cleared the tableau performer turned to childishly taunt the bomb with her fingers on her nose.

The legacy of the Windmill Theatre

When Laura Henderson died in November 1944, theater ownership was passed to Vivian Van Damm. He kept the performances running and helped enshrine the Windmill Theatre’s legacy and its contribution to morale throughout the war. When the conflict ended, it provided free performances for thousands of servicemen, and it stayed open into the 1960s, producing the same style of shows as during the war years.

Windmill Girls in evening gowns running from London’s Windmill Theatre to a party, 1953. (Photo Credit: PA Images / Getty Images)

Even though the theater closed in 1964, it lives on in film and on stage. Films include Tonight and Every Night (1945), Murder at the Windmill (1949), Secrets of a Windmill Girl (1966) and Mrs. Henderson Presents (2005). There is also a musical titled Mrs. Henderson Presents, which premiered in 2015.